This is Herstory.

Journey through the life of Nobuko Joanne Miyamoto.

“I grew up never hearing a song that sang me.”

-Nobuko Miyamoto

Uprooted.

As a third-generation Japanese American, I was a child uprooted by our forced removal during World War II. I heard songs I loved on the radio. Songs filled my loneliness, gave me joy, made me want to dance. I didn’t realize I was missing my own song.

When my family was released from camp, I was called JoAnne rather than

Nobuko, my real first name.

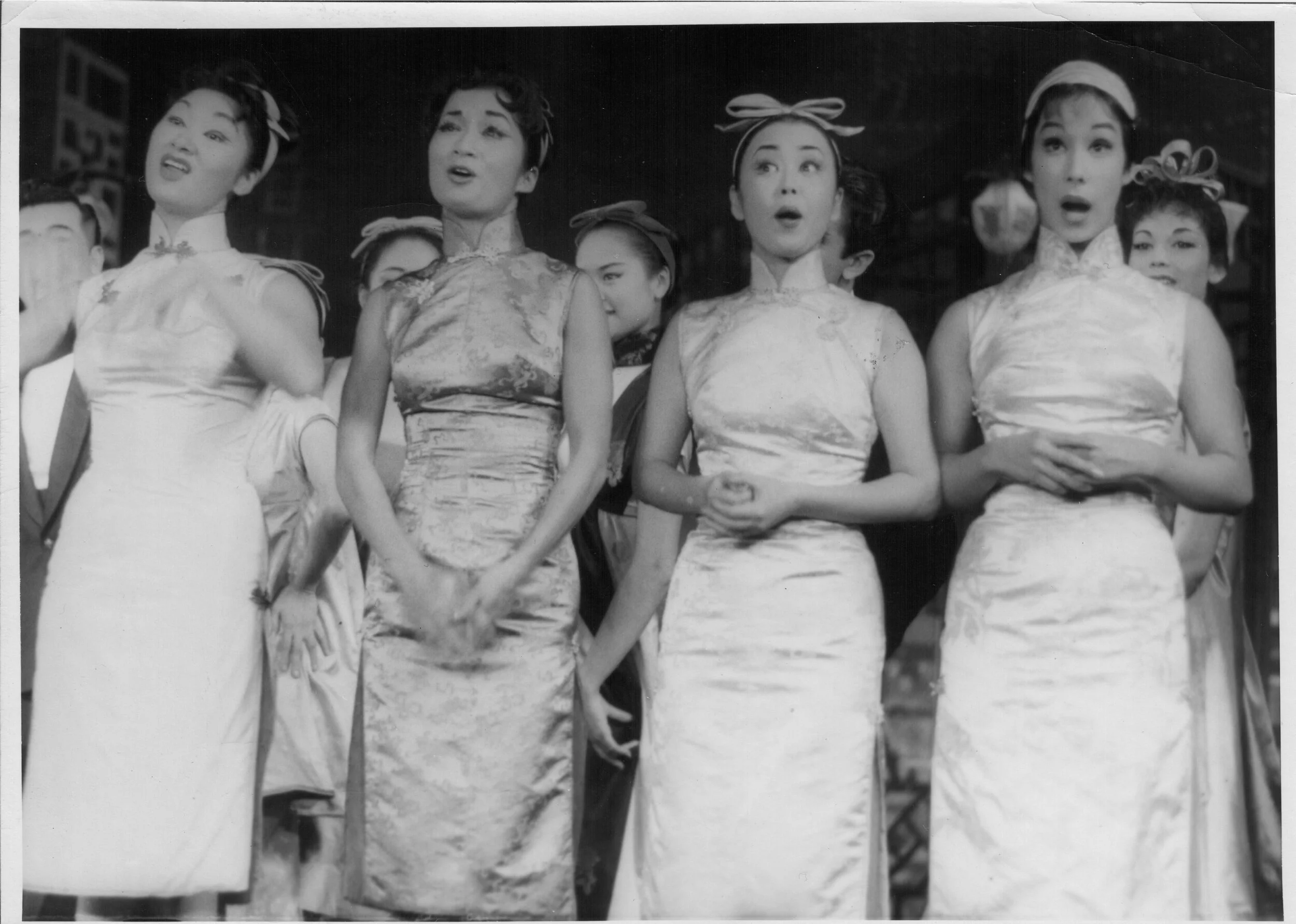

I was exposed to classical music and studied ballet. I thought the Japanese music my uncle chanted was weird. I was lucky to have a black music teacher at my grammar school, Mrs. Jackson, who believed children could sing Bach chorales. And so we did! I was also blessed with a scholarship at American School of Dance, which led to a career in films and on Broadway. At eighteen I was in the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical Flower Drum Song, singing directly to the audience, “Chop suey, chop suey . . . ” I didn’t know why I was feeling uncomfortable. There was something in the way those delighted folks looked at us. In a flash I realized, WE were “chop suey”—Chinese food for white people!

That started me questioning: how come I’ve never seen a show that told my story? Why do I have to play these silly “Oriental” roles?

My solution: Cross the color line. Maybe in this way, I could use my talent and be seen as someone besides an “Oriental.” In the early 1960s I did “pass” for Puerto Rican in the film West Side Story, where I was cast as one of Maria’s friends. It felt pretty exhilarating, but it also revealed to me a fear: I could sing in a group, but alone, I was afraid of the sound of my own voice. This led me to my singing teacher, Dini Clarke, an African American musician from Washington, DC. In the ’60s, while Watts was burning, he shared stories across his piano of discrimination he endured as a black man. And he introduced me to Billie Holiday, Lena Horne, Carmen McCrae, Nina Simone—black women singers who knew how to tell a story with a song.

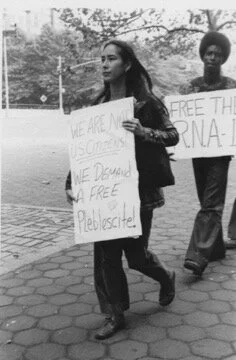

Pictured: Nobuko marching at the Republic of New Africa demonstration

Singing my song was not simply a matter of learning vocal technique. Breaking out of my silence was a process of understanding and undoing the oppression that put a muzzle on my people in this country. In 1968 I helped the Italian filmmaker Antonello Branca to make a docudrama about the Black Panthers. This project took me across another kind of color line, into the black struggle. In Harlem, I met activist Yuri Kochiyama, who brought me to a meeting of Asian Americans for Action. I was blown away by this group of intergenerational radicals who were taking a stand against the U.S. war in Vietnam. Among them was Chris Iijima, an articulate young activist who was one of their leaders.

In 1970 we went to Chicago to an historic gathering of East and West Coast Asian activists coming together for the first time. After intense meetings with the Panthers and urban Native Americans, a few of us late nighters were cooling down. Chris Iijima brought out his guitar. I didn’t know he played. He didn’t know I sang. Somehow we stumbled into making a song. It seemed the only way to sum up the communal feelings of that moment. The next day before this large congregation of activists, Chris and I sang, feeling a force beyond our own. It was the song we never had, the song we’d been waiting for. We were just there to deliver it.

“Chris and I sang, feeling a force beyond our own. It was the song we never had, the song we’d been waiting for. We were just there to deliver it.”

-Nobuko

In 1970 we went to Chicago to an historic gathering of East and West Coast Asian activists coming together for the first time. After intense meetings with the Panthers and urban Native Americans, a few of us late nighters were cooling down. Chris Iijima brought out his guitar. I didn’t know he played. He didn’t know I sang. Somehow we stumbled into making a song. It seemed the only way to sum up the communal feelings of that moment. The next day before this large congregation of activists, Chris and I sang, feeling a force beyond our own. It was the song we never had, the song we’d been waiting for. We were just there to deliver it.

Having our own song changed my life. It transformed how I saw art and what it could do in the world. It started me on my life’s path as a community “artivist.”

-Nobuko

Joining Forces.

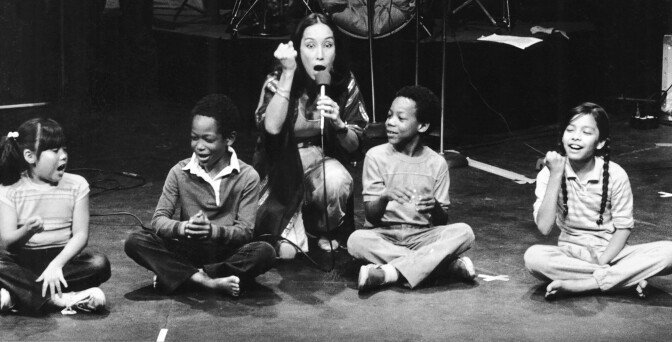

The many songs that followed led me and Chris to become troubadours, later joined by “Charlie” Chin. Sharing and learning with Asian American communities across the country, we were creating a voice for our people. We were not only performers, we were organizing, digging for our roots, defining our dreams to transform ourselves and our world. Our rootedness gave us the ability to sing our stories across cultural boundaries in a language of the spirit. It helped us create solidarity and support for struggles of other people of color. This was the fertile ground that birthed the 1973 album A Grain of Sand (Paredon)

Having our own song changed my life. It transformed how I saw art and what it could do in the world. It started me on my life’s path as a community “artivist.”

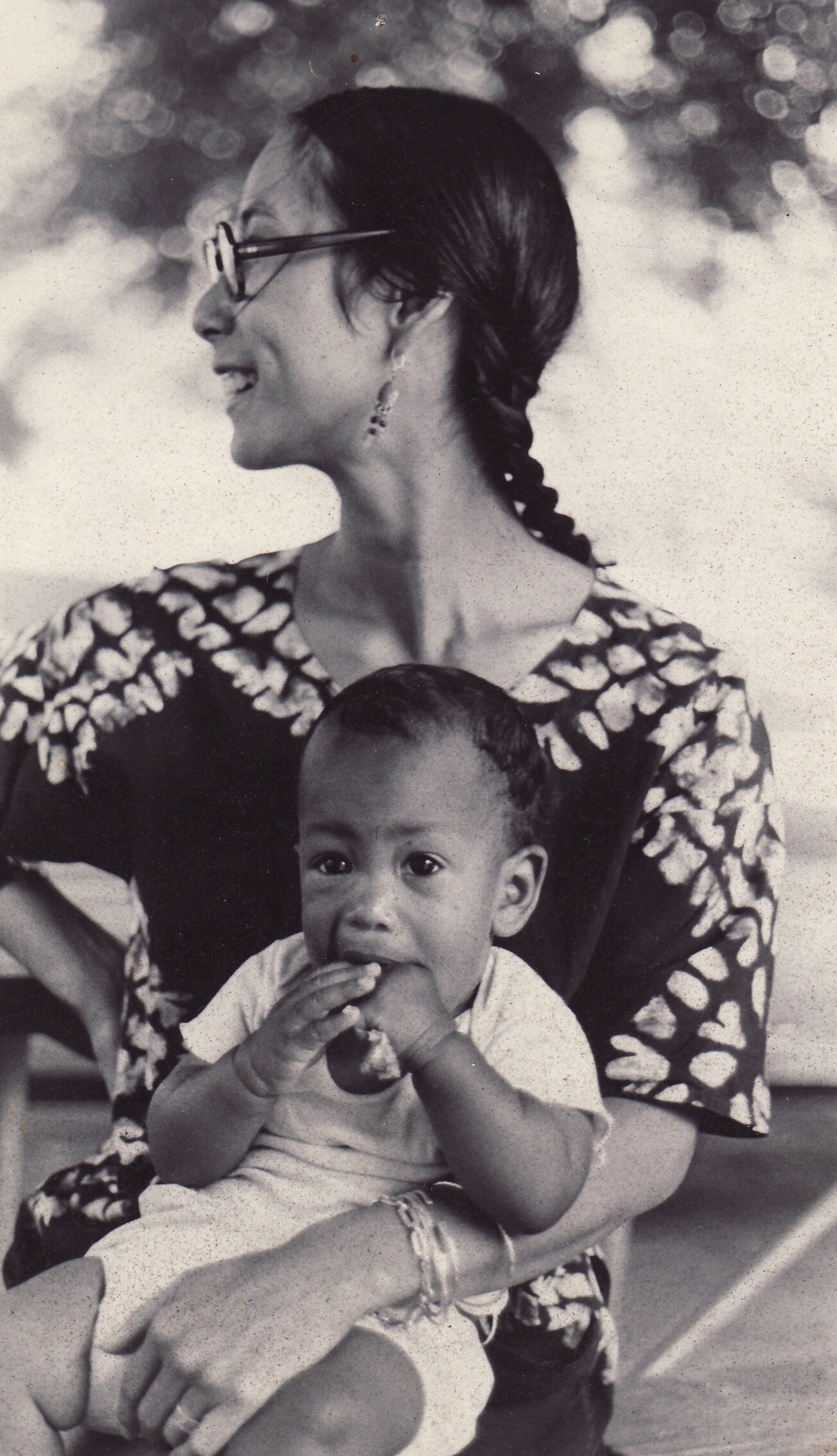

It has been a long journey, but I’m not rocking chair ready. I am an elder, a grandmother, a cultural activist, and still a song maker. One of my latest projects is a Smithsonian Folkways album, 120,000 STORIES. That’s a lot of stories, but not nearly enough. It is the number of Japanese Americans who were in concentration camps during World War II. But it also symbolizes the stories untold, the songs unheard, ignored, missing from our cultural stratosphere.

I sing for those like myself, who grew up without their own song. I sing for those different than myself, to share my story.

Above: Smithsonian Folkways Festival

Left: B.Y.O.Chopstix music video promo

“I sing for those like myself, who grew up without their own song. I sing for those different than myself, to share my story. I sing to open space for more songs, more stories – to reveal our humanity, our interconnectedness, and to touch the soul as only a song can do.”

— Nobuko Miyamoto

Read more about Nobuko’s story in her autobiography, “Not Yo’ Butterfly” available here.